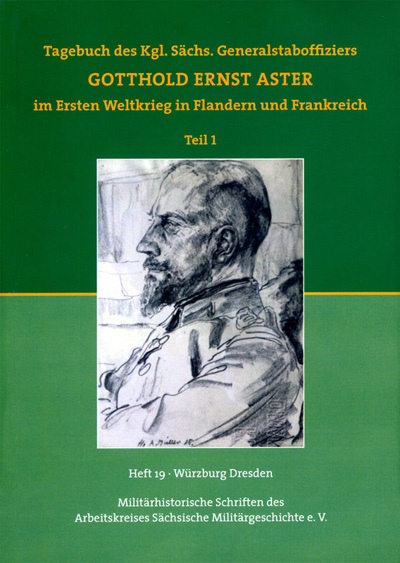

I recently finished reading this splendid volume published by the Arbeitskreis Sächsische Militärgeschichte e.V. Dresden. This group (full disclosure - I have since joined as their first UK-based member) is devoted to the study of the military history of Saxony in all periods, and runs a small WW1-focused museum in the gatehouse of the federal Bundeswehr museum in Dresden (which was the Royal Saxon Army's own museum until the end of the kingdom, and prior to that the Royal Saxon arsenal). The AKSMG also organised a travelling Christmas Truce exhibition in 2015 which visited Belgium and the UK, hosts regular lectures in its home city and even puts on Saxon living history events - at one of which I got to fulfill my dream of wearing the uniform of my great-grandfather's regiment in its original barracks (now the Saxon traffic ministry).

The AKSMG has been producing small books on its subjects of interest for years, and also prints and sells a very handy map of the barracks and other historic military buildings in Dresden. The diary of Major (later Oberst) Aster is their most ambitious project to date, a 250-page paperback including a few private photos of the author and his colleagues. It is in fact only the first of a planned two volumes, covering Aster's war from mobilisation until mid-May 1916 - at which point he was transferred to the Eastern Front as commander of Landwehr-Infanterie-Regiment Nr.107. This first volume will undoubtedly be the one of greater interest for British readers, covering as it does both the 1st and 2nd Battles of Ypres in considerable and grim detail. It is of course in German, and only printed in a small edition - but it is nevertheless one of the most interesting WW1 diaries I have read, and deserves as wide a readership as possible.

Major Aster was born in 1870 and joined the Kgl. Sächs. Kadettenkorps in 1885. Upon gaining his commission he served with Schützen-Regiment Nr.108, but was later seconded to the small Saxon detachment within Prussian Eisenbahn-Regiment Nr.2 (railway troops) in Berlin, to the Prussian Kriegsakademie and to the topographical section of the Prussian General Staff. As a fully-fledged officer of the Saxon General Staff he reached the rank of Major in 1910 while serving with 24. Infanterie-Division. Due to (unspecified) health problems however he chose to enter semi-retirement as an Offizier zur Disposition in 1911. Upon his recall at mobilisation he initially served in staff positions within Saxony - most interestingly (and lastly) working at the Saxon War Ministry in Dresden on the formation of the Saxon / Württemberg XXVII. Reserve-Korps, which represented those two kingdoms' contribution to the wave of new reserve formations beyond those allowed for in the mobilisation plans and consisting in large part of previously untrained Ersatz-Reservists and volunteers. As described in Jack Sheldon's The German Army at Ypres 1914 and our own Fighting the Kaiser's War - The Saxons in Flanders 1914-1918 these units were formed in an indecent hurry that makes the Kitchener divisions committed at Loos in 1915 look thoroughly well prepared in comparison. Aster is unsparing in his description of the bureaucratic obstacles and the acute shortages of materiel and of experienced personnel at every level which bedeviled the creation of the XXVII.RK. For his sins, he was soon appointed chief of staff with the 53. Reserve-Division - the purely Saxon one of the corps' two divisions (the other being the mixed 54.RD). He would hold this position until February 1916, surviving the replacement of both his corps and divisional commanders in the interim.

Aster is frank and unsparing in his assessments of the military situation and of his colleagues and superiors. Rest assured - the officers' corps of the Royal Saxon Army, and that of the German armed forces of which it formed a significant and idiosyncratic part were as riddled with professional rivalries and conflicts of personality as their British counterparts. As he describes it, it is remarkable that the XXVII.RK functioned at all. It is well known that the original Saxon corps commander Genltn. von Carlowitz broke down in October 1914 under the pressure of seeing his undertrained troops cut to pieces in the ceaseless attacks demanded by high command, but Aster reveals a hitherto unknown and serious conflict between Carlowitz' Prussian replacement General von Schubert and Aster's divisional commander Genltn. von Watzdorf. According to Aster the bitterly pessimistic von Watzdorf (whose peculiarities included an intense loathing for clergymen of any description) found himself sidelined by the relentlessly aggressive von Schubert, who summarily commandeered his forward command post and went over the heads of his subordinates to micromanage operations in the front line. Wounded in the backside by shrapnel whilst engaged in such activities, von Schubert earned himself the nickname 'General Hintendurch' (a pun on multiple levels in German, alluding to having been shot through (durch) the backside (hinten), implying failure and punning on the Eastern Front hero von Hindenburg). Friction between von Schubert, von Watzdorf and the brigade commanders persisted into 1915, culminating in complaints upwards from von Watzdorf to the staff of 4. Armee, the invocation of military judicial proceedings against several junior commanders and ultimately - to Aster's great relief - the replacement of von Watzdorf by the far more agreeable Gentln. Leuthold in summer 1915. However the appointment of Leuthold ultimately led to Aster's own replacement in February 1916, as the commander demanded a younger and healthier chief of staff who can cope with the expected rigours of mobile warfare. The remaining months prior to Aster's transfer to the Eastern Front were spent with XII. Armeekorps on the Aisne, filling in as a jobbing battalion and regimental commander with a series of Saxon infantry regiments.

The book is filled with impromptu tactical assessments of the situation as recorded in the heat of battle, as well as colourful anecdotes of rear-area life and the duties of a divisional staff officer. There is also a good deal of gossip and interesting accounts of meetings with everyone from the army commander Archduke Albrecht of Württemberg and the Saxon royal family to Dr. Prof. Fritz Haber, the father of gas warfare (Aster didn't much care for him). Aster's regular assessment's of Germany's strategic situation are less accurate (largely due to over-optimism) than his judgement of the state of his own front, but provide a fascinating insight into the prevailing views among German field officers at the time. He takes an intense interest in the Balkans, Eastern Front and the Ottoman fronts as well as the Western Front and shows a broad understanding of the economic and political dimensions of grand strategy. However it is quite striking how much that was going on further up the command chain was evidently obscured on a 'need to know' basis - as late as 29th February 1916 he assesses the Verdun offensive as a purely local operation by 5. Armee analogous to 2nd Ypres and intended to divert Entente forces from elsewhere.

The author's views are not what a British reader might expect of a German officer, but not so unusual for the Saxon officers' corps. He has a pronounced distaste for Prussian absolutism and in particular for the influence of the Kaiser on military operations, and welcomes the expected strengthening of the democratic element in Germany as an expected 'peace dividend' after the war. However he shows considerable personal fondness for the King of Saxony and his sons (all of whom appear in the book). He is prepared to admit the considerable military value of the Württemberg component in the XXVII.RK, and does not simply take the Saxon side unreservedly when friction between the two contingents is evident. He has much to say about the peculiarities of the Bavarian Army when his division is temporarily subordinated to Bavarian corps command - he finds them hospitable and highly efficient, but exceptionally pedantic and demanding in the volume of paperwork they expect. As for the enemy, Aster frequently expresses intense disgust at the British political leadership but has little hate for the fighting men opposite - except on occasions such as an instance in November 1914 when he believes (rightly or otherwise) that prisoners from his division have been killed out of hand. He expresses no distaste for gas warfare per se, but clearly has little faith in its reliability and a personal dislike for its (in his view) obnoxiously egotistical inventor.

In short - if you can read German, pick this up without question if you see it for sale anywhere. It richly deserves translation into English, but such a project is - sadly - certainly beyond the resources of the AKSMG.