NOTE: This piece is under reconstruction to incorporate additional sources and information. If you are a member of Colonel Joe Robinson's WW1 German history group on Facebook (which we warmly recommend to all our readers), you can read a more up to date version here. There is also another general piece in the same group on The Royal Saxon Army at Christmas: 1914-1918.

In Fighting the Kaiser’s War we only had limited space to outline the events of the 1914 Christmas Truce on the front of XIX. Armeekorps, the only Saxon corps to be facing the British at the time. In this article I attempt to pin down the locations all of the known accounts from this front, showing which British units faced which German ones and how the sources match up. I will continue to update it as fresh information comes to light!

Temporary tacit ceasefires also occurred with the French on the front held by XXVII.Reservekorps north of the Menin Road, and one French source describes a brief episode of fraternisation on the northern part of that front earlier in December. However the prolonged trucing and mass fraternisation that took place at Christmas 1914 between the troops of XIX. AK and their opponents were not replicated in any other Saxon sector.

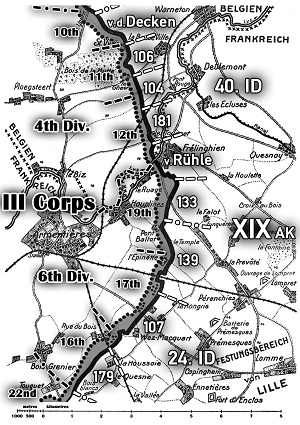

That Christmas XIX.AK held the front from the Douve in the north to the vicinity of Bois Grenier in the south with 24.Infanterie-Division on the left and 40.Infanterie-Division on the right. On the extreme right flank between the Douve and Ploegsteert Wood, several battalions of Bavarian and Prussian Jägers were attached to 40.ID as part of a composite 'Detachement von der Decken’ commanded by the staff of IR 134. As far as we could determine from the available German sources, the remainder of the corps front was held exclusively by its own organic Saxon units. Trucing and/or fraternisation occurred along most of this frontage. Most Saxon officers at all levels appear to have welcomed these developments, and to have been concerned chiefly with putting truces onto an official basis, preserving a degree of discipline and keeping up appearances against a possible adverse reaction from their superiors. Wherever possible truces were exploited productively to allow for the retrieval and burial of the dead, and to get other work done more easily and comfortably in the open.

It is important to note that major episodes of trucing and fraternisation also occurred both to the north and to the south of the Saxon corps. To the right / north of XIX.AK some Bavarian infantry of 6.bRD took part; to the left / south the Westphalians of Prussian VII.AK (comprising 13.ID on the right and 14.ID on the left) were heavily involved. Interestingly the Prussian units of VII.AK are often misidentified as ‘Saxons’ in British reports. Several such reports seem to indicate that this was not merely a misunderstanding on the part of the British, but a deliberate deception on the part of the Westphalians who had seemingly chosen to present themselves to the enemy as Saxons.

It is evident from passing references in British accounts prior to Christmas 1914 that the Saxons already had a good reputation with the enemy, based presumably on pre-war associations and on incidents earlier in the campaign - for instance the ceasefire for recovery of the wounded between 2nd Leinsters and IR 179 at Prémesques on 20 October. Conversely non-trucing Saxons could be misidentified by what the British took to be their ‘un-Saxon’ behaviour. At Rue du Bois Major Buchanan-Dunlop of 1st Leicestershires (16th Brigade / 6th Division) was facing both IR 107 and IR 179 of 24.ID - he correctly identified the former, fraternising regiment as Saxons (“jolly cheery fellows for the most part, and it seems so silly in the circumstances to be fighting them”) but misidentified the less friendly IR 179 as Prussians (“very vicious indeed”). British press coverage would subsequently emphasise the Saxon desire for peace and attempt to sow disunity between Saxony and Prussia, to the great professional embarrassment and annoyance of the officers of XIX.AK.

Verbal contact between the opposing sides was established in most cases on Christmas Eve, following the display of Christmas trees and lights in the German trenches and the massed signing which accompanied it. It is difficult to reconstruct exactly how this escalated to fraternisation in any given sector, as most available accounts from both sides are keen to assert that the enemy were the first to leave their trenches and the first to offer a truce. Most of the officers and men involved seem to have correctly surmised that the wrath of higher command was far more likely to descend on those who had actively initiated fraternisation and trucing, than on those who had just humanely accepted such an offer from the enemy. On the German side, a strict anti-fraternisation order was issued by OHL on 29th December, proclaiming that all unauthorised approaches to the enemy were to be punished as high treason. As a result, it became essential to put all local truces on a formal basis and to retrospectively justify the contact that had occurred within that framework. The most interesting result of this was a handwritten document handed to officers of 1st Rifle Brigade (11th Brigade / 4th Division) at Ploegsteert Wood and preserved in their battalion war diary. Signed by Oberst William Kohl of IR106 and authorised by “das zuständige Generalkommando” (meaning the corps staff - Generalkommando - of XIX.AK) it proposes an official truce over the New Year period in Kohl’s regimental sector for the specific purpose of recovering and burying the remaining dead of both sides from No Man’s Land; unfortunately the British were unable to meet Kohl’s conditions in time and the agreement never came into force.

Following the OHL order, some punishments were inevitably imposed on individuals subsequently caught breaking the rules on permissible contact with the enemy. Contrary to legend these punishments were neither widespread nor serious. For instance, when JB 10 was relieved by Saxon JB 13 just south of the Douve on 29 December, the latter unit found an unofficial truce in force and soon had to enforce the OHL order on its men:

As in our book (but at greater length) I will attempt to summarise events in each Saxon regimental sector in turn, indicating when and where the familiar British accounts fit into the story. These accounts can most readily be found in Brown & Seaton’s much-reprinted Christmas Truce, to which I will refer the reader for further details. I have not yet read Chris Baker’s book on the subject.

Note that following the fighting in October and November, the brigades, divisions and even regiments of XIX.AK were deployed in a somewhat disjointed and irregular manner; this would not be resolved definitively until both divisions were triangularised in March 1915 (donating IR 106, IR 107 and their parent brigade HQ to the new 58.ID, while reorganising 24.ID and 40.ID with one brigade of three regiments each).

Please refer to the Christmas Truce sector map (click the link to download the full-size version) for an approximate overview of German regimental and British brigade boundaries based on comparison of all available sources.

‘Detachement von der Decken’ (from the Douve to the St. Yvon road) was based around 10. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.134 (minus its II. Bataillon and one two-gun Zug of the MG-Kompagnie). The ad-hoc ‘detachment’ also controlled a varying number of Jäger battalions and cavalry engineering units left behind by the departing Höheren Kavallerie-Kommandeur 2 on the Saxons’ right. Field artillery was provided by 40.ID, with two 7.7cm field gun batteries and a single two-gun section of 10.5cm howitzers from FAR 32 and FAR 68 at Oberst von der Decken’s disposal.

On Christmas Eve the detachment’s front was held from north to south by Hannoversches Jäger-Bataillon Nr.10 (JB 10), Kgl. Bayer. 1. Jäger-Bataillon König (bJB 1) and III. / IR 134 - respectively holding Unterabschnitt (subsector) 'A', 'B' and 'C'. This Warneton sector map for 1914-1915 from the published history of JB 13 clearly shows the subsector boundaries, although not the trenches in 'C'; note also the sector boundary at the Yves-Strasse. In the cases of the Jäger battalions seemingly only one company per battalion was in the line, whereas III. / IR 134 had at least two (probably 10. and 11./134) deployed abreast. This Saxon battalion was supported by the detached MG-Kompagnie of 2. Schlesisches Jäger-Bataillon Nr.6 (MGK / JB 6; the main body of JB 6 was far to the south on the Argonne front). Since the end of November this machine-gun company had been deployed in positions forward of Damier-Ferme (see the Warneton sector map above), from which it contributed to the defeat of the British attack in the IR 106 sector on 19th December. There is nothing in the published histories of JB 6 and IR 134 to support the contention that MGK / JB 6 was with II. / IR 134 at Frelinghien that Christmas.

Facing Oberst von der Decken's force was 10th Brigade (4th Division) with (from north to south) 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Royal Warwicks in the front line. As numerous British accounts (including that of Bruce Bairnsfather) attest, all units on both sides were involved in the fraternisation here. However the published history of IR 134 states only that Christmas passed ‘peacefully’ and that of bJB 1 does not mention it at all. The only German account is from the history of JB 10 (published in 1933), which is surprisingly frank. According to this account, 4. / JB 10 took over the line about 9pm on Christmas Eve and brought their Christmas trees and lights with them. Contrary to claims by the Seaforths to have begun singing first, JB 10 describes the enemy ceasing fire and starting to call out to them in response to the German festivities. Hauptmann Richter, commanding 4. / JB 10, was alarmed by this development and strongly suspected a ruse. He immediately ordered his men to fire a volley at the enemy, which evidently went well over their heads (probably on purpose). This failed to deter the Scots, and eventually the English-speaking Oberjäger Echte met them at the wire; it is likely that he was the English-speaking German described by Corporal John Ferguson of the Seaforths in his famous account (see Brown & Seaton pp.61-62). Surprisingly British accounts tend to overlook the fact that JB 10 was recruited in Prussian-annexed Hanover, and bore the famous ‘GIBRALTAR’ cuff title commemorating the Hanoverian defence of that British fortress.

On Christmas Day further fraternisation occurred in conjunction with the burial of the dead (many of whom were French in this sector). Threats by Hauptmann Richter of punishments for fraternisation were quashed by the battalion commander.

4. / JB 10 was relieved by another company of the battalion on Boxing Day. On the night of 28th-29th December JB 10 was relieved by 2. Kgl. Sächs. Jäger-Bataillon Nr.13 and bJB 1 by Kgl. Bayer. 2. Jäger-Bataillon. Meanwhile the Seaforths had been relieved on the 27th by 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Royal Warwicks on the 28th by 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers. As noted above, the truce in this sector persisted into early January, although (according to JB 13) further fraternisation was suppressed.

7. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment ‘König Georg’ Nr. 106 (from the St. Yvon road to the Le Gheer road) actually belonged to 24.ID, but had only arrived from the Champagne front in late October while the battle was already raging - and had consequently been used to reinforce a critical part of the existing front of 40.ID opposite Ploegsteert Wood. The regiment had taken the edge of the wood on 7 November, but due to appalling weather had gradually abandoned its untenable line there in favour of a new position constructed behind them by Saxon engineers (3. Komp. / Pionier-Bataillon 22) around the hamlet of Le Pelerin. The last advanced posts in the wood were abandoned on 19th December, the sentries falling back to Le Pelerin in the face of a major assault by British 11th Brigade. This attack broke up with grievous losses in front of the well-fortified Saxon position, known to the British as ‘the Birdcage’ (due to its - by 1914-15 standards - thick belts of wire) and to the Germans as ‘der Entenschnabel’ (‘the Duck’s Bill’, due to the shape of this small salient).

In December the IR 106 sector consisted of two battalion subsectors, divided by the Le Pelerin road (Fabrikstrasse). The northern subsector was held alternately by I. and III. / IR 106, the southern subsector alternately by II. / IR 106 and the attached II. / IR 133. Given the number of sightings in the British sources (although the regimental histories are unclear), it appears that II. / IR 133 was holding the southern half over Christmas. Opposite IR 106 (and II. / IR 133) was most of 11th Brigade (4th Division), comprising from north to south 1st Somerset Light Infantry, 1st Rifle Brigade with the London Rifle Brigade attached and 1st Hampshires.

It seems that the singing in this sector began quite late on Christmas Eve. The regimental band under Musikmeister Capitän played that night at La Basse Ville, beginning about 4am according to accounts from JB 10. Contact with the enemy seems to have been established informally during the night. On Christmas morning a provisional sector truce was agreed with officers of the Somerset Light Infantry and Rifle Brigade for the purpose of recovering the numerous dead scattered between Ploegsteert Wood and the ‘Birdcage’ for burial. Captain Beckett of the Hampshires later reported that he had kept his men in their trenches, did not interfere with the truce and carefully observed the mass fraternisation that ensued (Brown & Seaton pp.217-219). The regimental history of IR 106 (published in 1927) states that:

Any such permission from XIX.AK was surely retrospective, since (going by his journal entries) the first report reached Generalmajor Richard Kaden at the headquarters of 48. Infanterie-Brigade (which comprised IR 106 and IR 107) on 27th December. Admittedly IR 106 was operating detached from its parent brigade and division at this time, meaning that Kaden was not quite as well informed as usual about its doings. He had no objections to the situation, having already heard about the truce in the IR 107 sector (see our forthcoming book for extended extracts from Generalmajor Kaden’s journal). Despite his own clear acquiescence to the truce, Oberst Kohl of IR 106 was obviously anxious to keep his regiment’s contact with the enemy on a strictly formal (and militarily defensible) basis. On 27 December he ordered a symbolic resumption of MG fire at MG at midnight, of which the Hampshires (and presumably the other British units opposite) were politely warned in advance. On the 30th the Hampshires were informed by the Saxons that they would no longer be able to fraternise, and that symbolic firing might be required (Brown & Seaton pp.168-169). The same day the Rifles were given the aforementioned New Year truce proposal, signed by Kohl and authorised by Generalkommando XIX.AK. Although the British could not fulfil Kohl’s conditions in time, the sector remained quiet well into early January.

5. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment ‘Kronprinz’ Nr.104 (from the Le Gheer road to the vicinity of the railway line) held this sector with its I. and/or II. Bataillon; III. / IR 104 was detached with ‘Regiment von Rühle’ at Frelinghien as described below. At Christmas the IR 104 sector lay opposite 1st East Lancashires of 11th Brigade and partly opposite 2nd Monmouthshires of 12th Brigade.

The published history of IR 104 describes events here in a very guarded tone.

Sources from both British battalions unanimously describe a burial truce and fraternisation on Christmas Day, quite possibly following the example of events in the IR 106 sector. We have not yet seen any account which purports to explain exactly when and how the ‘ice was broken’ between IR 104 and their opponents. According to Lieutenant (later Brigadier) C.E.M. Richards of 1st East Lancashires, the battalion staff took part in the fraternisation (much to his disgust) and he received orders that evening to prepare a football pitch in No Man’s Land for New Year’s Day (Brown & Seaton p.139). The irregular order was never carried out. Tragically Private Palfrey and Sergeant Collins of 2nd Monmouthshires were killed by snipers in No Man’s Land on Christmas Day, possibly due to the less friendly attitude of the neighbouring IR 181 (Brown & Seaton pp.105-106). According to Richards, hostilities recommenced that evening, and there are no accounts of fraternisation here after Christmas Day. However the war diary of 1st East Lancashires describes subsequent days as ‘all quiet’ and only indicates that sniping had resumed on the 31st.

The Monmouthshires were relieved by 2nd Essex on the evening of Christmas Day.

15. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.181 (from the vicinity of the railway line to the vicinity of Le Touquet) faced 2nd Monmouthshires and 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers of 12th Brigade. According to its published history the regiment ‘most energetically rejected’ all fraternisation approaches.

Nevertheless a report from Lieutenant-Colonel Cuthbertson of 2nd Monmouthshires (which admittedly contains a few plainly impossible unit identifications in addition to some highly plausible ones) claims that a few men from 10. / IR 181 were present at the burial truce in the IR 104 sector (Brown & Seaton pp.219-221). 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers certainly fraternised, although this may have been with III. / IR 104 of ‘Regiment von Rühle’ immediately to the south of IR 181. Accounts from the Lancashire Fusiliers of a German envoy being taken prisoner on Christmas Eve (due to a sentry’s error in not blindfolding him before he was brought into the British lines) may have some connection to the apparently hostile attitude of IR 181; they may also be the source of the reference in the published history of IR 104 to ‘trusting German soldiers’ being deceived into captivity (Brown & Seaton pp.130-131).

‘Regiment von Rühle’ (from the vicinity of Le Touquet to somewhat south of Frelinghien) was an ad-hoc formation commanded by Hauptmann Rühle von Lilienstern of IR 134. Its sector around the town of Frelinghien on the Lys was held by III. / IR 104 and II./ IR 134 on the northern and southern banks, respectively facing 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers (12th Brigade / 4th Division) and 2nd Royal Welsh Fusiliers (19th Brigade / 6th Division).

As noted above the Lancashire Fusiliers certainly fraternised on Christmas Day; according to their published history, ‘A’ Company played a game of football against the Saxons with an old tin (Brown & Seaton p.137). Events on the south bank are much more extensively documented on the British side, although as noted above the published history of IR 134 is highly reticent. The Royal Welsh Fusiliers put up an improvised ‘Christmas card’ on a sheet of canvas on Christmas Eve (Brown & Seaton p.54), and when the fog cleared early in the afternoon of Christmas Day the Saxons began to call across to them. Captain Stockwell met his counterpart, “Count something or other” (possibly Hptm. Wilhelm Graf Vitzthum von Eckstädt of IR134) in No Man’s Land, and beer from Frelinghien brewery was donated to the Welshmen in return for a plum pudding (Brown & Seaton pp.119-121).

Hostilities were theoretically renewed on Boxing Day, but the sector remained quiet; the Welsh were relieved by 2nd Durham Light Infantry of 18th Brigade that evening.

9. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.133 (from somewhat south of Frelinghien to slightly north of Pont Ballot) held its relatively large sector presumably with I. / IR 133 and III. / IR 133 abreast; II. / IR 133 was attached to IR 106 at Ploegsteert Wood as noted above. Opposite the regimental sector lay 2nd Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, 1st Cameronians and possibly also the territorial 1/5th Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), all of 19th Brigade.

A published history of IR 133 did not appear until 1969, by which time its author Leutnant Johannes Niemann had already appeared in a BBC documentary on the Truce (‘Christmas Day Passed Quietly’, 1968). The elderly officer was also apparently responsible for tracking down another eyewitness from his regiment, Soldat(?) Hugo Klemm, whose account he received in a letter in 1968 (Brown & Seaton p.256).

According to Niemann and Klemm, events on Christmas Eve only escalated to the point of a ceasefire and long-distance singing contest between the opposing trenches. Klemm notes that he and his comrades had been warned in advance by their company commander to be on their guard against any enemy attempt to take advantage of their relaxed mood (Brown & Seaton pp.55-56). However according to the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, contact was established by envoys in No Man’s Land that night. One such envoy was German-speaking Lieutenant Ian Stewart, who brought back a photo of the pre-war IR 133 football team from the exchange of gifts - indicating that the idea of football was already in the air here on Christmas Eve (Brown & Seaton pp.63-64).

Whatever may have been agreed during the night, Klemm claims that in his part of the line an NCO of IR 133 ‘broke the ice’ early on Christmas morning by carrying a tree out into No Man’s Land and meeting a Tommy there. His platoon commander (one Leutnant Grosse, not yet identified in the Ranglisten) then met his counterpart between the lines to agree a burial truce (Brown & Seaton pp.83-84). For his part, Niemann was informed about midday that mass fraternisation was already in progress and went out to investigate. His account of subsequent developments includes the most detailed (and perhaps the most plausible) description of a Christmas Truce football match, during which the Saxons were greatly amused to discover that the Scotsmen really were wearing nothing underneath their kilts! Football is also mentioned in passing by Klemm. Supposedly the Saxons won 3-2, a score which recurs frequently in British references to Christmas football matches. A version of Niemann’s own account (much shorter than the one in his regimental history) can be found in translation here. It does not include his description of how the fraternisation ended:

To the south of the Argylls, 1st Cameronians took no part in the truce or fraternisation with either IR 133 or IR 139 - apparently under the illusion that they were opposite Prussians (Brown & Seaton pp.103-104). The territorial 1/5th Cameronians however did fraternise on Christmas Day - unfortunately I am still uncertain whether the forward element of this battalion was attached on the left or right of 1st Cameronians (or possibly even both), so it is unclear which of the Saxon regiments was involved. Be that as it may, this instance of fraternisation came to a tragic end after ‘a regular’ (possibly a member of the 1st Cameronians?) fired at the Germans, and a return shot killed Corporal Walter Smith. Saxon protestations that 'a Prussian' was responsible are scarcely credible based on the known unit dispositions, unless referring to an individual Prussian subject serving with the Saxon army (Brown & Seaton pp.106-107).

The Cameronians (including the 1/5th) were relieved by 1st East Yorkshires and the Argylls by 2nd Sherwood Foresters on Boxing Day; both relieving units belonged to 18th Brigade.

11. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.139 (from slightly north of Pont Ballot to La Bleue / La Hongrie) had at least two battalions in line, and had shifted northward on 5th December to take over the former sector of JB 13 at Pont Ballot. At Christmas 1914 it faced the right flank of the Cameronians (see IR 133 above), as well as 2nd Leinsters and 3rd Rifle Brigade both of 17th Brigade (6th Division).

At the northernmost end of the IR 139 sector, low-level hostilities continued throughout as normal - and (as partly noted above) both 1st Cameronians and ‘D’ Company of 2nd Leinsters mistakenly believed they were opposite Prussians. However on the front held by ‘B’ and ‘C’ Company of the Leinsters, together with that of the neighbouring 3rd Rifle Brigade, the British responded warmly to Saxon carol singing and decorations on Christmas Eve. Both a British account (Brown & Seaton pp.62-63) and the regimental history of IR 139 (published in 1927) agree that fraternisation occurred between that regiment and the Rifles in No Man’s Land that night. According to IR 139, the British were the instigators and a British chaplain was the first to approach them; this has not been corroborated from British sources. While British accounts of the Truce often mention Germans with family or business connections in England, the history of IR 139 claims that a few of the Tommies they met that night had worked in Chemnitz (home town or IR 104 and IR 181) in spring 1914. According to this source, a truce was agreed until midday on Boxing Day, which would include the artillery ‘as far as possible’ while recognising that neither side’s infantry could make definite guarantees for the actions of their sister arm.

On Christmas Day fraternisation and the recovery of the dead for burial took place on a large scale, and the Leinsters also became involved (Brown & Seaton pp.110, 129 & 140; see also the Leinsters’ regimental journal for December 2008). There was a brief panic when Oberst Einert of IR 139 chose to visit his regiment in the trenches. Having not informed regimental HQ of the truce, the officers on the ground attempted to restore the appearance of normality before his arrival. Their deception came unravelled when Einert ordered a sentry to shoot a Tommy who was digging in the open; naturally the shot went wide and the Tommy started gesticulating with his spade - either imitating the signal for ‘missed’ in range shooting or reminding the shooter of the truce. This anecdote is repeated in Brown & Seaton (pp.108-109), but they partly overlook the humorous tone and entirely omit the outcome - since it was no longer possible to keep up the deception, Einert was informed and fortunately saw the funny side.

The Leinsters were relieved by 1st West Yorkshires of 18th Brigade on Boxing Day. Trucing and low-level fraternisation continued here into early January. Interestingly 2nd Leinsters (by then transferred to 24th Division) once again truced and fraternised with Saxons (IR 178 / 123.ID) at St. Eloi in November 1915. On a third occasion at Vimy Ridge in September 1916, Saxons (probably from RIR 101 / 23.RD) attempted to fraternise with a sentry of the battalion, but were treacherously shot after being encouraged to approach. Captain F.C. Hitchcock, who had taken part in the fraternisation at St. Eloi (with the intention of gathering information) recorded the incident at Vimy Ridge with apparent approval (see Hitchcock, “Stand To” A Diary of the Trenches 1915-1918 pp.119-126, 182).

8. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment ‘Prinz Johann Georg’ Nr.107 (from La Bleue / La Hongrie to the railway line at Rue du Bois) had all three battalions in line - from north to south III. / IR 107 (holding Wez-Macquart), II. / IR 107 (holding Epheu-Ferme) and I. / IR 107 (facing the town of Rue du Bois itself). They may have been partly facing the 3rd Rifle Brigade, and were certainly facing the 1/16th Londons (Queen's Westminster Rifles) and 1st North Staffordshires, likewise of 17th Brigade. At Rue du Bois on their left they also partly faced 1st Leicesters of 16th Brigade. All of these units are known to have fraternised with IR 107.

It was this sector where the most extensive and prolonged fraternisation occurred. However immediately prior to Christmas IR 107 was on high alert, in the expectation that the British might attempt a surprise attack during the celebrations. At 1am on 24th December a demolition team blew up a house directly in front of the German lines on the Rue du Bois itself (the main road through the village of the same name) to clear the field of fire. However the afternoon and evening proved peaceful. According to numerous British sources, the Tommies responded enthusiastically to the regiment’s singing and decorations, and soon both sides were out on their respective parapets singing and calling to each other; incidents of fraternisation naturally followed (see Brown & Seaton pp.65-69). In a letter to his wife Captain R.J. Armes of 1st North Staffordshires later described how he met a Saxon officer in No Man’s Land to agree terms for a burial truce (Brown & Seaton pp.68-69); Generalmajor Kaden identifies this officer as Ltn. Horst von Gehe (subsequently killed in action as a fighter pilot with Kampfstaffel 26 at Mercy le Bas on 17th March 1916). Both sources agree on the terms of the truce, which was to extend until midnight British time (1am German time) on the night of 25th-26th December.

Generalmajor Kaden also adds that the truce decreed that neither side was to enter the other’s lines. Nevertheless that night first four, then a further two drunken Tommies stumbled into the lines of III. / IR 107 (Wez-Macquart - La Bleue) and were taken prisoner; these are believed to correspond to three men of the Queen’s Westminster Rifles (Privates Noel Byng, Herbert Goude and Pearce) and three of the 3rd Rifles(Corporal Thomas Latimer and two others), all of whom ‘went missing’ on Christmas Eve and were later reported captured (see Brown & Seaton p.66). Kaden describes two of them in his diary, and claims that they took part in the regimental distribution of gifts behind the lines that same night!

According to the regimental history the burial truce at Rue du Bois began promptly at 9am on Christmas Day. The fighting here had been extremely bloody, especially on the 28th October when IR 107 briefly took the town but was too depleted to hold it. With the aid of the enemy, many of the dead were successfully identified and given a proper burial that Christmas. Meanwhile fraternisation gradually developed all along the regimental front, and took increasingly curious forms - many of the most colourful British stories of the Christmas Truce originated here (see Brown & Seaton pp.82, 99, 101-103, 108, 111, 137-140). Officers and men wandered about freely in numbers too large to be controlled by the authorities on either side. Rather unsportingly, Major Arbuthnot of 24 Battery Royal Field Artillery took the opportunity to reconnoitre Wez-Macquart and identify future targets while disguised as a German (Brown & Seaton p.128).

The truce was officially ended by the British firing four small shells at the agreed hour (Brown & Seaton p.141). However this was clearly no more than a symbolic gesture. A regimental order for IR 107 to resume hostilities at midday on Boxing Day was courteously passed on to 1st North Staffordshires by a junior officer, and resulted only in a brief and harmless token volley (Brown & Seaton pp.148 & 162). While normality (albeit somewhat subdued) was restored along the rest of the regimental front, the unofficial truce at Rue du Bois persisted as a fait accompli and was pragmatically exploited by IR 107 to get as much work as possible done on the trenches in the open. Nevertheless it must have been an uncomfortable situation for the regimental staff following the dissemination of the OHL anti-fraternisation order. Numerous British anecdotes indicate that fraternisation and even visits to the British trenches (in numbers too great for those involved to be taken prisoner) had not ended. The corps staff would certainly have been horrified had they known that HRH Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony (the youngest of the King’s three sons) and a fellow staff officer had been among those visitors (see s.K.H. Prinz Ernst Heinrich von Sachsen, Mein Lebensweg vom Königsschloss zum Bauernhof pp.77-78; this anecdote can only conceivably refer to the Rue du Bois sector).

The Queen's Westminster Rifles were relieved by 1st Royal Fusiliers on Boxing Day, and rejoined 18th Brigade.

14. Kgl. Sächs. Infanterie-Regiment Nr.179 (from the railway line at Rue du Bois to Grande Flamengrie Farm) was not involved in the truce, as attested by every available source from both sides. Most of British 16th Brigade (6th Division) was opposite, with 1st Leicesters on the British left mainly facing IR 107 while 1st Buffs and 2nd York & Lancasters faced IR 179.

The main text of the published history of IR 179 merely states that Christmas Eve was undisturbed by the enemy, who could be heard celebrating with singing and bagpipes. However according to a personal account from a veteran of 9. / IR 179 (included in the published regimental history), his company was expecting a relief that evening. While waiting they sang Christmas songs, and were applauded by the British. No trees are mentioned (presumably because the men were not expecting to remain there long) but candles were produced and a seasonal atmosphere developed. However the non-appearance of their relief but the 179ers in a foul mood, under the influence of which they turned from Christmas carols to an exchange of catcalls with the enemy.

The war diary of 2nd York & Lancasters records (formal?) “advances for armistice” on Christmas Day which they rebuffed. IR 179 nevertheless observed developments in the IR 107 sector with interest, and did not attempt to disrupt what the published history of IR 179 characterises purely as an official truce for burial of the dead. However there is no reference in this book (or any other source we have yet seen from XIX.AK) to the known occurrence of trucing and fraternisation in the sector of the regiment’s southern neighbour, IR 55 (13.ID / VII.AK).

The Buffs were relieved by 1st King’s (Shropshire Light Infantry) on Boxing Day.